America in the Crosshairs: The Emergence of Destabilization as Global Strategy

A game‑theoretic investigation of Russian interference, Israeli influence, Epstein’s network, and the hollowing of US democracy

Overview

This piece pulls together stories most people only see in fragments: Russian trolls and bots, the grinding war in Ukraine, Israeli covert influence campaigns in the US, and the shadow world around Jeffrey Epstein. Instead of treating them as separate scandals, it looks at them as moves in the same strategic game.

Using basic game theory, the article asks a simple question: if you are a state or a powerful network that cannot beat the United States head‑on, what is the smartest way to weaken it? The answer that emerges is destabilization from within: erode trust, deepen polarization, compromise key elites, and keep Washington tied up in costly, divisive foreign commitments.

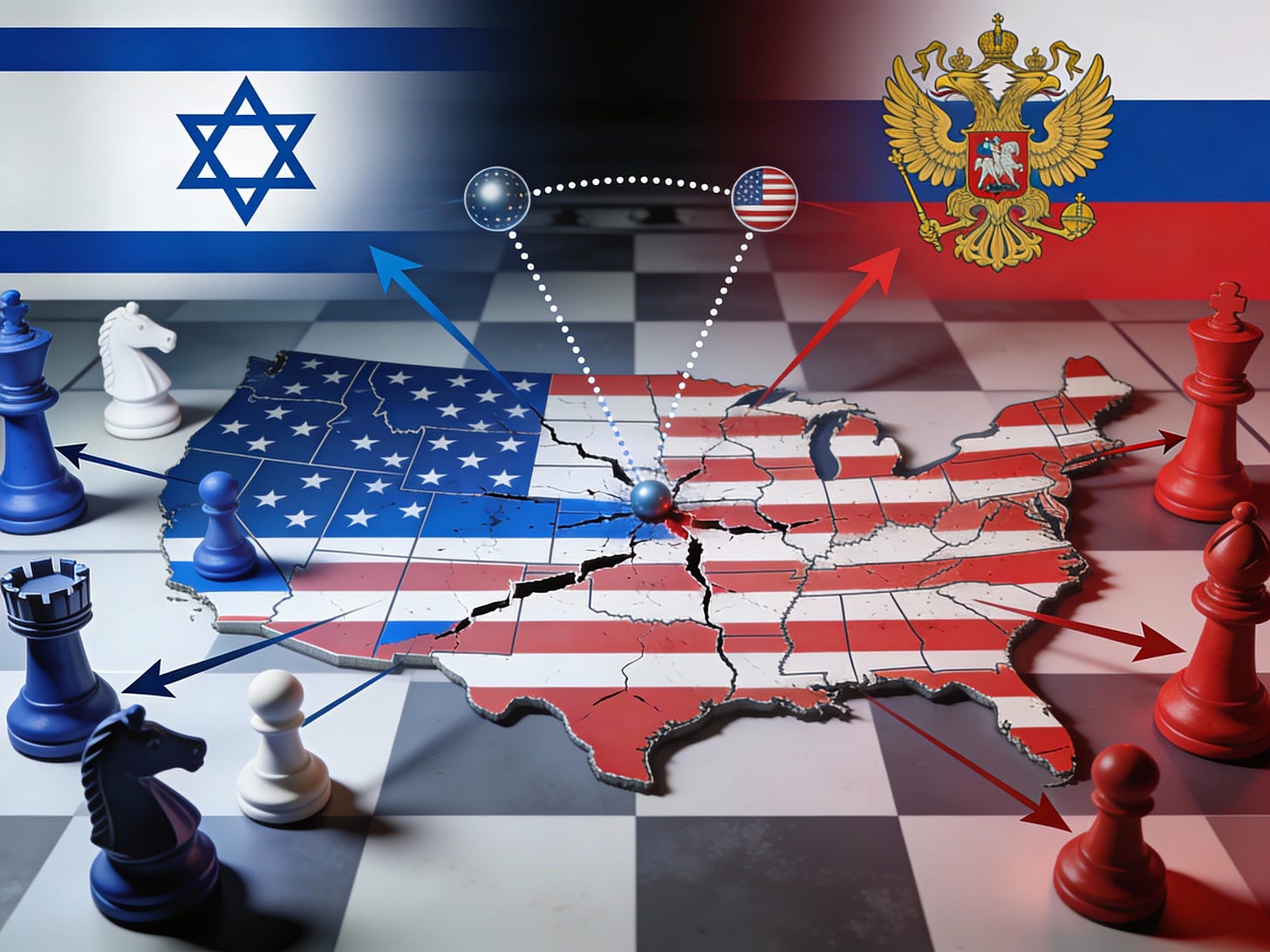

What follows is not a single conspiracy theory, but a map of how Russia, Israel, and transnational elites each play their own games on the same vulnerable board: American democracy.

PART I: THE GAME NO ONE ADMITTED WAS BEING PLAYED

In early 2026, as new Jeffrey Epstein related documents began surfacing in courts and in newsrooms on both sides of the Atlantic, the familiar outlines of a scandal suddenly looked stranger. The headlines were predictable enough: more transcripts, more names, more sickening detail about trafficking, abuse, and impunity. But buried alongside the salacious material were clues that pointed somewhere else.

There were repeated references to Russia. There were discussions of visas and meetings in Moscow. There were notes implying that Epstein had offered analysis and “insight” on US politics to officials connected to the Kremlin. At the same time, older threads about Epstein’s proximity to Israeli political and intelligence figures resurfaced. His investments in surveillance technology firms with roots in Israeli military intelligence. His longstanding friendship with a former Israeli prime minister who once ran the country’s military intelligence branch. The shadow of Ghislaine Maxwell’s father, Robert Maxwell, long suspected of juggling relationships with multiple intelligence services.

Overlay those details on what we already know. Since at least 2014, Russia has run a sustained campaign to undermine US democracy and transatlantic unity. It has done this through election interference, disinformation, cyber intrusions, and now a grinding war in Ukraine that hits Western economies and politics like a slow earthquake. Other authoritarian states have studied and copied parts of this model. And now, as revealed in 2024, even an American ally such as Israel has engaged in covert digital influence operations against US lawmakers and citizens, using anonymous networks and artificial intelligence to shape opinion on Gaza and military aid.

On the surface these stories seem disconnected. A sex criminal with mysterious friends. A Russian troll farm buying Facebook ads. A war in Eastern Europe that will not end. An Israeli ministry quietly funding fake American accounts to lobby Congress. But if we view them through the lens of game theory, they begin to line up.

Game theory is not about predicting exact events. It is about understanding structures. Who are the players. What do they want. What constraints do they face. What options do they have. And crucially, how does the fact that others are also strategic shape their choices.

In the world that emerged after the Cold War, the United States is structurally dominant. It has the largest military budget, the main reserve currency, and an unmatched global alliance network. For any rival, direct confrontation is suicidal. The rational response for weaker powers is not to fight the US head on, but to play a different game entirely. A game where the target is not US tanks or aircraft carriers, but the nerves, cohesion, and decision making capacity of US society itself.

Russia has embraced that game openly. Other rivals have followed. Even some allies have borrowed its techniques when pushing their own agendas. And transnational elite networks, of which Epstein’s circle was one ugly expression, provide leverage points where foreign and domestic interests can blur.

The thesis that emerges is not that there is a single, unified plot commanded from a hidden room in Moscow or Tel Aviv. It is that a growing number of actors now see the destabilization of the United States, or at least the manipulation of its internal politics, as part of their rational strategy. The result is that America finds itself under sustained strategic pressure. Not from a lone gun pointed at its head, but from a crossfire of overlapping moves, all nudging in the same direction.

To see how this works, we need to look at Russia’s doctrine of political warfare, at the economic and psychological impacts of the Ukraine war, at Israel’s covert operations in the US information space, and at how a network like Epstein’s fits into a broader picture of elite capture.

Along the way we will use a few simple game theoretic ideas. Not to dress up speculation in mathematics, but to force clarity about motives and payoffs. Once that structure is visible, the scattered dots begin to connect.

PART II: RUSSIA AS THE WEAKER PLAYER, AND WHY DESTABILIZATION MAKES SENSE

In any game where one player is much stronger than the others, the weaker players face a dilemma. If they play by the stronger player’s preferred rules, they are likely to lose. If they escalate openly, they risk destruction. The rational path often lies in asymmetric strategies, which take advantage of the strong player’s blind spots and vulnerabilities.

That is the position Russia has been in since the 1990s. The Soviet Union collapsed. NATO not only survived but expanded. The Russian economy shrank, its armed forces hollowed out, its political system lurched from chaos to restoration of a hard authoritarian regime. At the same time, the US and its allies continued to extend their reach through economic institutions, treaties, military bases, and what is often called “soft power”: culture, technology, finance, and ideology.

Inside Russian military academies and think tanks, a new consensus formed. If Russia is to contest US influence, it must do so primarily in the information and political domains, not only on the battlefield. Russian strategists have used terms such as “non linear war” and “information confrontation” to describe this arena. It includes cyber operations, propaganda, manipulation of media, support for sympathetic or disruptive political actors abroad, and the exploitation of diaspora communities and business ties.

In formal game theoretic language, this is a shift from a symmetric contest of capabilities, where both sides pile up similar kinds of resources, to an asymmetric contest, where each side emphasizes what the other is structurally bad at defending.

The US is highly capable at projecting military power across oceans. It is less capable at protecting the integrity of its domestic discourse when that discourse runs through privately owned, profit driven platforms that algorithmically reward outrage and division.

The US can outspend Russia easily on tank brigades and fighter squadrons. It cannot easily outspend the problem of its own internal mistrust, segregated information ecosystems, and decaying media institutions. That is not a budget issue. It is a social architecture issue.

In this context, Russia’s strategic options look different from the US ones. Moscow cannot win an arms race, but it can try to make Washington’s arms harder to use by making the US political system unpredictable, angry, and fragmented. The target is not the hard power of America. The target is its will and its ability to use that power coherently.

Seen that way, Russian interference in US elections and domestic debates since at least 2016 is not a one off aberration. It is part of a rational, repeated strategy. Each election cycle, each social conflict, each scandal offers new chances to move the needle by a tiny amount.

Imagine a repeated game with the following features:

Russia chooses how much to invest in covert political operations in a given period: hacking, leaks, troll activity, support to fringe actors, and so on.

The US chooses how much to invest in defenses and in visible punishment of interference, and how much to invest in repairing its own internal weaknesses.

The outcome is some change in US domestic cohesion, in the legitimacy of its institutions, and in the credibility of its elections.

If Russian decision makers perceive that interference is cheap, that US defenses are patchy, and that punishment will be limited or inconsistent, then the best response is to keep interfering. From their point of view, not interfering looks like leaving easy gains on the table.

That is how a destabilization strategy turns into a long term equilibrium. It continues not because every single move yields spectacular rewards, but because the costs are low, the risks are uncertain, and the potential upside is large. Even small shifts in public opinion, or small increases in cynicism, can matter when accumulated over years.

This is why US intelligence leaders have repeatedly testified that Russia views its 2016 and 2020 operations as successful enough to keep trying. The goal was not necessarily to elect a specific candidate and then retire from the field. The deeper goal was to convince Americans that their democracy is for sale, their media is fake, and their political opponents are traitors, so that any future US government, no matter who leads it, finds it harder to act.

PART III: BOTS, TROLLS, AND THE CHEAP TALK STRATEGY

Within this destabilization game, bots and trolls are the most visible move. They also help illustrate how game theory thinks differently about cause and effect than everyday commentary.

A typical media story asks: did Russian bots decide the 2016 election. That is the wrong question. The more relevant question is: in a repeated game, what does systematic, low cost manipulation do to the beliefs and coordination of players over time.

To see why, consider what we actually know.

Investigations by reporters, tech companies, and US government bodies revealed that Russia’s Internet Research Agency created thousands of fake accounts across Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube. These accounts posed as Americans of different political stripes. “Blacktivist”. “Heart of Texas”. “Army of Jesus”. Pro Trump and anti Trump pages. Pro police and anti police communities. They bought ads, organized events, and reached tens of millions of users.

Classic political science would ask: did exposure to these specific pieces of content cause people to change their vote. That is extremely hard to measure. Some studies suggest small direct effects on specific groups. Others find no measurable impact on overall vote choice.

The game theoretic view steps back. It notes that the Russian effort was persistent, adaptive, and targeted at fault lines that already existed. Racial tensions. Immigration anxieties. Gun culture. Identity politics. Distrust of media and elites. It also notes that these operations were cheap compared with tanks and missiles.

In a cheap talk game, signals have little direct cost and may or may not be truthful. They nevertheless influence players’ beliefs and expectations, which then influence actions. Everyday examples include rumors that start a bank run, gossip that ruins a reputation, or viral hoaxes that cause people to panic buy fuel.

Russian bots are a form of cheap talk designed to change America’s internal expectations about itself. If enough people come to believe that “everyone is corrupt”, that “every protest is a foreign plant”, or that “elections are theater”, then coordination on constructive politics becomes harder. Civic participation becomes less attractive. More energy gets diverted into fighting symbolic culture wars.

The other side of the game is that bots and trolls are not operating in a vacuum. They sit on top of a media ecosystem already incentivized to maximize engagement. US based clickbait farms that spam partisan content are functionally indistinguishable from foreign troll farms at the level of user experience. If you are just scrolling, a provocative meme looks the same whether it was generated in Saint Petersburg or San Antonio.

This interaction is key. Russian operators do not need to invent new divisions. They simply surf the waves already generated by domestic actors. They introduce slightly more extreme versions of existing narratives. They inflame arguments that are already underway. In game terms, they are not changing the rules. They are changing the payoffs on the edges, making it slightly more rewarding for domestic players to engage in maximalist, conspiratorial, or apocalyptic rhetoric.

Over a single election cycle, this might only move the dial slightly. Over several cycles, it can produce lasting damage. Trust, once eroded, is slow to repair. Polarization, once baked into identities, is hard to reverse.

Cheap talk also interacts with what economists call selection effects. The people most likely to see and share Russian content are already those deeply embedded in political subcultures. It is not that Russia swings the median voter directly. It is that Russian campaigns help harden the extremes, which in turn pull the center apart.

From the perspective of Russian strategists, there is another advantage. Cheap talk is deniable. When confronted with evidence of troll farms and bot networks, Moscow can dismiss it as hysteria or claim that everyone does it. That ambiguity complicates the US response. Game theorists who study foreign election interference have shown that clear, credible threats of retaliation can sometimes deter the most aggressive forms of interference, such as tampering with vote counts. But when the activity is mostly propaganda and microtargeted manipulation, red lines are fuzzier.

The net result is a kind of background radiation of manipulation. It does not dictate outcomes. It degrades the quality of the environment in which those outcomes are decided.

PART IV: THE UKRAINE WAR AS A STRATEGIC PRESSURE CAMPAIGN

If Russian bots are daily moves, the war in Ukraine is a multi year play that affects payoffs in a deeper way. Once again, game theory helps clarify why Moscow might persist in a conflict that has been so costly on the battlefield.

Since February 2022, Ukraine has fought for its survival. The US and European allies have provided financial support, weapons, training, and intelligence. The total US appropriation for Ukraine related efforts is in the hundreds of billions of dollars spread over several years, with the majority earmarked for security assistance.

In terms of raw capacity, the US and its allies can sustain such support for a long time. The absolute numbers are large, but relative to total Western economic output and government budgets, they are manageable. This is one reason some strategists call support for Ukraine “the best defense bargain in decades.” For a small fraction of NATO’s combined defense budgets, Russia’s military has been severely degraded.

However, the real action is not only on the military balance sheet. It is in the indirect effects on Western societies.

The war severely disrupted global energy markets. Russia is a major exporter of oil and gas. Ukraine is a major exporter of grain and other commodities. Sanctions, supply chain shocks, and the closing and reopening of routes through the Black Sea all contributed to spikes in fuel, fertilizer, and food prices. Central banks recorded surges in inflation. Households from Berlin to Boston felt it in gasoline prices, home heating bills, and grocery store receipts.

Economists have tried to disentangle the drivers of that inflation wave. Pandemic related disruptions. Corporate pricing power. Fiscal stimulus. The war is only one factor among several. But it is a highly visible one, easy to connect in the public imagination: news footage of burning Ukrainian cities, then a bigger number on the gas station sign.

Russia cannot control all these dynamics. But it can count on them. By choosing a full scale invasion, and then by choosing to continue the war across multiple winters, the Kremlin has imposed a constant low level economic and political tax on the West. That tax is not enough to break Western economies. It is enough to feed fatigue and division.

Within the logic of repeated games, Ukraine becomes a stage where Western unity and staying power are tested. Each new aid package requires votes in parliaments, negotiations among allies, and sales pitches to skeptical publics. Each new round of escalation or counter escalation provokes arguments over risk and restraint.

From Moscow’s perspective, the war creates several political levers:

It amplifies anti interventionist and isolationist currents in US and European politics.

It sharpens divides between hawks and doves within parties and coalitions.

It provides content for disinformation campaigns that portray Ukraine as irredeemably corrupt, Western leaders as hypocritical, and the war as a money laundering scheme.

It offers opportunities for transactional deals with states that would like to exploit Western distraction or energy volatility.

Even in a scenario where Russia cannot achieve its maximal military aims, prolonging the conflict can still be rational if it continues to damage Western unity and if it supports a domestic narrative in Russia that justifies authoritarian rule as necessary for survival.

There is another layer. The Ukraine war has revealed that a prolonged, high intensity conflict is possible in Europe in the 21st century even under nuclear shadow. That fact alone changes how other actors think about the risks and rewards of coercion. It normalizes a world in which wars of choice can be used as pressure campaigns, provided they stop short of triggering nuclear exchange.

In that world, the US is drawn into repeated dilemmas. If it supports a victim of aggression, it risks being portrayed as an empire that drags its allies into endless wars. If it hesitates, it is portrayed as weak and unreliable. In either case, Russia’s goal of making US leadership look both costly and morally compromised advances.

In game theory, this is sometimes modeled as a contest of endurance. Who can sustain losses, in different currencies, for longer. Russia loses soldiers, matériel, and economic opportunities. The West loses money, political cohesion, and a share of global influence. Victory is not defined strictly by territory on maps, but by who emerges with more freedom of action and more credibility.

From that vantage point, Ukraine is not just a humanitarian catastrophe and a geopolitical crisis. It is a theater in which the destabilization strategy plays out in slow motion.

PART V: ISRAEL’S TWO LEVEL GAME INSIDE AMERICAN POLITICS

Russia is an adversary. Israel is an ally. Both, however, are players in the same global game. Both have discovered that, under contemporary conditions, manipulating US politics is sometimes easier and cheaper than persuading US leaders in open forums.

To understand Israel’s behavior, we need to see it as a small but militarily powerful state facing multiple threats and entangled in domestic turmoil. Its leaders must constantly juggle at least three sets of constraints:

External security threats, including Iran, Hezbollah, Hamas, and others.

International diplomatic pressures, including from the US, Europe, and regional players.

Domestic political pressures, including coalition instability, protests, and ideological polarization.

Political scientist Robert Putnam captured this kind of situation with the concept of “two level games.” Leaders negotiate at the international level, but any agreement they make must also be ratified by some domestic process, whether formal or informal. That means both their foreign partners and their domestic opponents shape what is feasible.

For Israel, US domestic politics is effectively part of its own domestic constraint structure. If the US Congress is strongly pro government in Israel, Israeli leaders have more freedom to expand settlements, launch operations, or ignore international criticism. If US politics shifts, even slightly, toward conditioning aid or criticizing conduct more harshly, Israeli leaders’ win set, the range of deals they can accept without being punished at home, shrinks.

This helps explain why some parts of the Israeli state apparatus decided to engage not just in overt public diplomacy and normal lobbying, but in secret digital influence operations that impersonated Americans.

In 2024, the exposure of a covert campaign run by an Israeli ministry and executed by a Tel Aviv based marketing firm provided a clear example. The operation used fake accounts, AI generated personas, and microtargeted messaging to push pro government narratives and to attack dissenters in the US. The target set included more than a hundred and twenty US lawmakers, especially Democrats critical of the conduct of the war in Gaza. The false identities posed as US citizens and presented their views as local, organic sentiment.

This operation was not on the scale of Russia’s 2016 interference. It was smaller and more focused. Its goal was not to install a specific US president, but to harden congressional support for Israeli war aims and against calls for restraint.

Still, the method is telling. In a world where Russia has already normalized the idea that foreign states can and should quietly manipulate American social media, Israel, frightened by its own international isolation and by growing criticism in parts of US society, reached for the same tool kit.

Game theory again highlights the incentive. If one state is already interfering, the cost of abstaining rises. If Israeli officials convinced themselves that Russia, China, Iran, and others are already eroding America’s information defenses, they may have concluded that playing by cleaner rules would be self defeating. In effect, they decided that to protect their own interests they had to become, in a limited way, part of the destabilization ecosystem.

Once that threshold is crossed, it is easy to generalize. If it worked in 2024, why not again. If AI powered influence can protect an aid package, why not use it to help a friendly candidate survive a primary challenge. The logic of repeated play, with little punishment, pushes in one direction.

The strategic danger for the US is not only what adversaries do, but what friends learn from them. As more states conclude that covert manipulation of US discourse is a rational choice, the baseline level of interference rises. The domestic public cannot easily distinguish messages from Moscow, messages from Tel Aviv, messages from Beijing, and messages from partisan US actors who now imitate their methods. All they see is a steady flood of content, much of it anonymous or deceptive, all of it claiming to represent “ordinary citizens.”

In such an environment, accusations of foreign interference themselves become weapons. Genuine exposure of a foreign influence campaign can be dismissed as partisan hysteria. Genuine domestic dissent can be smeared as the work of foreign bots. That, too, serves the destabilization strategy, whether or not it was intended.

Israel’s role in this story is not that of a mastermind intent on destroying its patron. It is that of a worried, embattled ally that, in seeking to lock in American support, adopts tools that further corrode American democratic resilience. The effect is still to keep the US under constant pressure from multiple directions.

PART VI: EPSTEIN’S WORLD AS A STRATEGIC PLATFORM

The Epstein saga is often treated as an aberration, a grotesque side story of individual depravity. That framing is comforting. It suggests that once he and Ghislaine Maxwell were imprisoned, the system that enabled them could be closed and forgotten.

Viewed through the strategic lens developed so far, that comfort looks misplaced. Epstein’s life and connections reveal the outlines of something larger and more important: a way in which power, money, and intelligence interests overlap in private spaces that are almost completely unaccountable. Those spaces are ideal for a certain kind of game.

To see this, consider several features of Epstein’s world.

First, his guest lists and social circles. They included current and former heads of state, senior politicians from multiple countries, billionaires, leading scientists, prominent lawyers, media owners, and members of royal families. People who decide, or influence, war and peace, regulation and deregulatory waves, technology policy, surveillance norms, and financial rules.

Second, his real estate and transportation assets. A private Caribbean island. A Manhattan townhouse. A large property in New Mexico. A private jet fleet whose flight logs show dozens and dozens of high profile names. These are places and vehicles where normal oversight does not reach. There is no C‑SPAN camera on a flight between Teterboro and Paris. There is no ethics watchdog in a villa on a private island.

Third, the criminal pattern itself. Recruitment of vulnerable young women and underage girls. Use of intermediaries and fixers. Continual crossing of borders with minimal interference. A legal system that repeatedly gave Epstein deals and benefits that ordinary offenders never receive.

Fourth, the intelligence shadows. A father figure for Ghislaine who was long suspected of having worked with multiple intelligence services. Investments in companies that offered surveillance and emergency response technology to governments, with leadership drawn from the ranks of Israeli signals intelligence veterans and Western tech elites. Long term proximity to individuals known to shuttle between public intelligence work and private consulting.

It is not necessary to sort out which allegation about which dinner, which meeting, or which business relationship is factual and which is speculation to see the structural pattern. Epstein’s network connected powerful agents who controlled large amounts of political and financial capital, in spaces that generated secrets and vulnerabilities, under the gaze of people who knew how to trade in secrets and vulnerabilities.

This is classic territory for what game theorists call games of incomplete information. Players do not fully know each other’s type. That is, they do not know exactly how corruptible, reckless, loyal, or fearful the other person is. Interactions produce signals that help update those beliefs.

Now add the possibility of recording devices, informal witness networks, or simply the accumulation of shared complicity. Each time a powerful figure crosses a line in a semi private space, each time they accept favors or travel that looks questionable on paper, each time they gossip or boast, information is created that could be used against them.

You now have the conditions for a leverage platform. No single intelligence agency needs to own it outright. Different agencies, and private intelligence firms, can attempt to penetrate and monitor different parts of it. An oligarch’s fixer may want dirt on a Western regulator. A state security service may be interested in a defense official or a scientist. A rival politician may simply want kompromat to wield in an internal power struggle.

This is not speculative in the abstract. The history of intelligence work is littered with honey traps, kompromat files, and cases where sex, money, and politics intersect in ways that leave participants exposed. What is distinctive about Epstein’s operation is the density of global elites involved, the length of time it persisted, and the way it overlapped with finance and technology.

From the point of view of foreign powers seeking to influence the United States, a platform like this is a strategic gift.

Imagine you are a Russian or Israeli or other intelligence planner thinking in game theoretic terms.

You can spend years trying to groom a single mid level official, with uncertain payoff. Or you can piggyback on a system where dozens of high level figures voluntarily congregate in environments suited for blackmail and pressure. Even if you only manage to access a fraction of that ecosystem, the leverage potential is enormous.

In a principal agent framework, the American people are the principal. They delegate authority to elected leaders and to appointed officials. Foreign powers want to distort the incentives of those agents, without the principal’s knowledge, so that they act partially in the foreign power’s interests.

Blackmail is one of the most direct ways to do that. But even without explicit blackmail, the knowledge that someone has visited a certain island, flown on a certain jet, or socialized in certain ways can create a kind of anticipatory obedience. The fear of future exposure can make an agent more cautious in opposing the preferences of those who might hold information.

This does not mean that every guest in Epstein’s circle was subject to blackmail. Many may have simply misjudged, or been arrogant enough to believe they were untouchable. It does not require all of them to be compromised for the platform to be useful. A few well placed targets can have ripple effects through entire bureaucracies.

From this perspective, the question of whether Epstein was primarily serving one intelligence service or another may be less important than the recognition that his world fit perfectly into the destabilization game that Russia, and others, are playing.

A United States whose decision makers are more compromised, more fearful, and more easily manipulated is a United States that is less able to resist pressure. It is more likely to make bad bargains, to tolerate corrosive foreign influence, and to shy away from cleaning up its own corrupt structures. That makes it a more attractive target for further interference.

In the earlier parts of this article, we saw how bots and trolls can slowly erode public trust and how a war like Ukraine can slowly erode political will. Epstein’s network shows how elite compromise can slowly erode the internal integrity of the state itself.

These three levels fit together. When public opinion is saturated with cynicism, when policy is distorted by external pressures from war and energy shocks, and when key decision makers carry hidden liabilities, the whole system begins to resemble a rigged game. That perception, in turn, feeds further cynicism, making foreign manipulation easier. A feedback loop takes shape.

PART VII: ELITE CAPTURE AND THE BROKEN PRINCIPAL AGENT CHAIN

To understand why this feedback loop is so dangerous, and why it is such an attractive target for foreign strategic planners, we need to turn more explicitly to the problem of elite capture.

In the simplest democratic ideal, the chain of accountability runs clearly. Citizens have interests. They choose representatives who, in exchange for power, are supposed to promote those interests. Bureaucrats carry out policy under legal constraints. Media organizations inform the public. Courts act as referees.

In reality, every link in that chain is vulnerable to what political economists call principal agent problems.

The principal has goals but cannot directly monitor the agent’s actions. The agent has more information about what is possible and about his own behavior than the principal does. The agent can then exploit that information advantage to pursue his own agenda, while pretending to serve the principal’s.

Elite capture is what happens when this problem becomes systematic rather than occasional. A small group of actors, who control resources and information, manage to bend institutions toward their own narrow interests. They do this through legal methods such as lobbying, campaign finance, think tank funding, and revolving doors between public office and private profit. They also do it through illegal or semi legal methods such as bribery, insider trading, conflicts of interest, and blackmail.

Foreign powers who want to destabilize a democracy do not need to build their own parallel governing apparatus. They can work within elite capture dynamics that already exist. They identify key agents whose incentives have drifted far from the public interest and offer them additional side payments: contracts, business opportunities, political support, kompromat insurance, or safe havens.

Game theoretic models of elite capture and information distortion show that when elites are in a position to filter or manipulate the information that reaches citizens, they can shift policy systematically away from what the public would choose under full information. They can also shape what issues dominate attention, deflecting scrutiny away from their own behavior.

Combine that with the information operations described earlier. A foreign intelligence service that wants to protect a captured elite network in a target state does not need to convince the entire population to love it. It simply needs to create enough confusion and noise that accusations and revelations about that network can be dismissed as partisan or conspiratorial.

In practical terms, this might look like the following sequence.

A set of powerful individuals become entangled in a scandalous network. Some of that entanglement has foreign fingerprints on it.

Journalists, activists, or honest officials begin to investigate.

Foreign and domestic actors with an interest in protecting that network deploy their resources to muddy the waters. They fund legal challenges, flood social media with counter narratives, promote alternative scandals, and cultivate sympathetic media voices.

At the same time, public opinion has already been weakened by years of disinformation. Many citizens are predisposed to believe that everything is a setup, that all sides are equally corrupt, or that the real story is something else entirely.

The result is a situation in which even serious revelations struggle to generate lasting consequences. A few people fall. The deeper patterns remain untouched.

From the foreign strategist’s angle, this is a win. The target country remains formally democratic, but practically paralyzed. Its elite is discredited enough that its moral authority is low, yet secure enough that it continues to make decisions that serve narrow interests. That combination makes it easier to manipulate.

The Epstein network can be seen as a concentrated microcosm of this larger issue. It shows how far elite capture can go when there is no effective constraint. It also shows how deeply foreign and domestic power structures can interpenetrate.

Now consider that this is only one known case. There are surely others, less extreme, that never become household names. Private equity dinners where regulatory favors are traded for future board seats. Arms deals where intermediaries tied to foreign intelligence services shape which weapons get sold to whom. Surveillance technology exports that give authoritarian governments the tools to track dissidents, with little scrutiny from the legislatures that nominally control such trade.

Each such pattern is an opportunity for foreign destabilizers. Each is a place where the American principal agent chain can be pulled further out of alignment.

PART VIII: A WORLD OF MANY PLAYERS, ONE TARGET

Up to this point, Russia has been at the center of the analysis, with Israel appearing as a more ambiguous, sometimes aligned, sometimes conflicting player. In reality, the network of destabilization is more crowded.

China conducts its own influence operations in the US, sometimes open and sometimes covert. These range from paid supplements in major newspapers to clandestine police stations that monitor diaspora communities. Iran pushes disinformation narratives about US domestic politics and about its own role in the Middle East. Gulf monarchies spend lavishly on lobbying and image laundering campaigns that blend into the fabric of Washington.

Private actors join in as well. Social media influencers, some knowingly and some unwittingly, amplify narratives crafted by foreign states. Corporate actors fund narratives that support their market objectives, which sometimes align with foreign strategic interests. Think tanks and universities accept foreign donations that come with subtle expectations.

In this crowded field, the United States is the primary target not because everyone agrees on what outcome they want, but because everyone recognizes that shifting American behavior can help them on their own separate boards.

For Russia, a more fractured, inward looking US is less able to expand NATO, enforce sanctions, or support color revolutions in Russia’s near abroad.

For China, a US consumed by internal conflict has less bandwidth to push back against Chinese moves in the South China Sea, Taiwan, or Africa.

For Iran, a US that is weary of intervention and skeptical of alliances is one that might eventually leave the region to its own balance of terror.

For certain policymakers in Israel, a US political class that treats unwavering support for any Israeli government as a litmus test is one that will not easily tie aid or diplomatic cover to conditions.

For multinational corporations, a US focused on cultural and personality conflict is one that may be slower to regulate monopolies, surveillance, or tax evasion.

These interests do not align perfectly. Sometimes they clash. But they often overlap around one practical aim: a United States that is less cohesive, less trusted by its own citizens, and less predictable in its foreign policy.

Write this in the language of game theory and it becomes clear why destabilization is so tempting. In a multi player game where one player is dominant, many of the others benefit from moves that reduce that dominance, even if they do not coordinate. They can free ride on each other’s actions.

Russia invests in bots and a war that drains attention. China invests in economic entanglement and narrative influence. Other states and non state actors develop and deploy their own variations. Each of these efforts has its own primary objective. Taken together, though, they add up.

The destabilization of the US is not a coalition project. It is an emergent outcome of many actors following their own narrow logic.

This is perhaps the most unsettling aspect. If there were a single plot, taking down a single mastermind would in theory solve the problem. In a system like the one we have, success in removing one malign actor leaves the structure intact, ready to be exploited by the next.

Epstein goes to jail. Others step into similar roles. A Russian troll farm is sanctioned. Others evolve and copy its methods. An Israeli operation is exposed. Another ministry, in another capital, learns from its mistakes and tries again with better cover.

In mathematical terms, this is an equilibrium. Not a moral equilibrium or a politically stable one, but a strategic one. No single actor has enough incentive to unilaterally stop playing the game of manipulation, because doing so would put it at a disadvantage relative to others who keep playing.

What this means for the US public is that the sense of being constantly targeted and manipulated is not paranoid. It is a realistic reading of the modern environment.

The more that sense spreads, however, the more dangerous the situation becomes. Citizens who come to believe that all politics is a foreign psyop, that every scandal is a plant, that no information is trustworthy, are citizens who are easier to control through fatigue and apathy.

Here too, foreign and domestic interests can align in perverse ways. Domestic elites who do not want to be held accountable for their own actions may happily embrace narratives that blame everything on foreign interference, even when they themselves are beneficiaries of that interference.

The end result is a world in which ordinary Americans are trapped in a hall of mirrors, unsure which messages are real, which loyalties are sincere, and which institutions they can trust. That uncertainty is itself a strategic weapon.

PART IX: GAME THEORY AND POSSIBLE ESCAPE ROUTES

If this is the game the US finds itself in, the natural question is whether the rules can be changed.

Game theory is sometimes caricatured as fatalistic. In truth, one of its core lessons is that changing the payoff structure can change the equilibrium. If destabilization becomes more costly and less beneficial, rational players will search for other strategies.

That does not mean the US can simply decree that foreign interference will stop. It does mean that it can make a series of moves that increase the price of playing the destabilization game and, at the same time, reduce the vulnerability of its own system.

These moves can be grouped into several categories.

The first is hardening the information environment. This is not about censorship. It is about authentication, transparency, and friction where needed.

Platforms can be required to verify and label political advertisers and to disclose more about the origin, targeting, and funding of campaigns. Tools that detect coordinated inauthentic behavior can be deployed more aggressively, not only against networks linked to adversaries, but also against those linked to allies or domestic actors. Users can be given clearer indicators when content comes from known propaganda outlets or from bots.

Done badly, such steps can be abused by incumbents to silence dissent. Done well, they increase the cost to foreign operators of impersonating locals and force them to rely more on overt channels, which are easier to monitor and respond to.

The second category involves repairing the principal agent chain.

This means stricter conflict of interest rules for lawmakers, judges, and senior officials. Harder walls between public office and certain private sector roles. Much more aggressive enforcement of laws against foreign bribery, money laundering, and unregistered agent work. Enhanced whistleblower protections for those inside elite networks who attempt to expose wrongdoing.

If élites know that their side deals and hidden entanglements are more likely to be discovered and punished, they will think twice before entering into compromising relationships with foreign interests.

It also means rethinking how campaign finance works. The current system, in which vast sums wash through super PACs, nonprofits, and lightly regulated digital advertising, creates constant opportunities for hidden influence. Tightening those flows, or at least making them much more transparent in real time, would starve some of the channels through which external actors currently operate.

The third involves foreign policy signaling.

The US has historically been inconsistent about punishing foreign interference. It has imposed sanctions in some cases, looked away in others, and treated allies differently from adversaries. From a game theory perspective, such inconsistency erodes deterrence. Other players cannot form clear expectations about what moves will trigger what consequences.

A more credible posture would require the US to lay out and then follow through on specific responses when certain lines are crossed, regardless of who crosses them. Coordinated inauthentic information campaigns that impersonate US citizens could be one such line. Attempts to bribe or blackmail elected officials could be another. Sanctions, visa bans, and public exposure are all tools that can be used. The key is that they must be used predictably enough to change incentives.

The fourth category is domestic renewal.

Foreign destabilization strategies work best when the target society is already brittle. The deeper causes of American vulnerability lie in decades of rising inequality, deindustrialization, racial and regional divides, and a political system that often appears unresponsive to everyday concerns.

Addressing those issues is not a quick fix. It requires investments in public goods, from healthcare and education to infrastructure and community institutions. It requires political reforms that make representation more proportional and competitive. It requires rebalancing the relationship between capital and labor.

From a narrow strategic standpoint, however, there is a clear payoff. A society that offers its members a more secure and dignified life is one where extremist narratives, foreign or domestic, find less fertile ground. People who believe their system, however flawed, can still be improved are less likely to embrace the fatalism that foreign propaganda encourages.

Finally, there is the question of transparency itself.

One of the greatest weapons foreign destabilizers have is secrecy. The secrecy of their own involvement, and the secrecy of the elite arrangements into which they tap. Bringing more of that hidden world into the open is both risky and necessary.

Investigations into networks like Epstein’s are part of that. So are disclosures about influence operations carried out by allies. So are attempts to track and report on the flows of anonymous money into US politics and civil society.

Not every revelation will be clean. Not every investigation will be fair. But the alternative, in which these structures operate entirely in the shadows, is worse.

In some game theoretic models, transparency changes the entire structure of the interaction. When players can observe each other’s moves and types more accurately, opportunities for deception shrink. When citizens can observe more of what their agents are doing, the space for elite capture narrows.

Of course, transparency that is weaponized to produce performative outrage and then quickly forgotten will not help much. The challenge is to build institutions and habits that turn exposure into sustained reform rather than just temporary scandal.

PART X: AMERICA UNDER THE GUN

The picture that emerges from this analysis is not a comforting one, but it is clarifying.

The United States is not facing a single existential enemy bent on its destruction by any means necessary. It is facing a strategic environment in which many actors, foreign and domestic, have learned that subtly weakening US cohesion and corrupting its elites can serve their interests.

Russia sits at the center of this environment as the most aggressive and shameless practitioner of the destabilization strategy. It uses bots and trolls to sow division. It uses a long war in Ukraine to impose economic and political costs that accumulate over time. It probes and exploits vulnerabilities in elite networks, including those touched by scandals like Epstein’s.

Other states, including adversaries such as China and Iran and allies such as Israel, have adopted variations of similar tools, even when their ultimate goals differ. They run information campaigns, lobby silently, fund proxies, and in some cases cross lines into covert manipulation of US discourse.

Within the US, powerful private actors and networks have built systems of influence and impunity that are easily exploited from abroad. The same shared dinners, private jets, and shell companies that connect billionaire donors to politicians also connect those politicians to foreign capital and interests.

Citizens, for their part, are bombarded by contradictory narratives. They are told that election interference is the greatest threat, and that it is a hoax. That their institutions are under attack, and that their institutions are the real enemy. That their leaders are compromised, and that anyone who says so is a dupe of foreign propaganda.

In this atmosphere, the idea that “America is under the gun” of a destabilization strategy is not hyperbole. It is descriptive. The gun is not a single rifle held by a single sniper. It is an array of pressures, exposures, and provocations that steadily narrow the country’s room to act and weaken its trust in itself.

Game theory does not tell us what will happen next. It does, however, warn about the dangers of staying in the current equilibrium. If destabilization remains a cheap and powerful move, more players will choose it. If elites remain easy to capture and compromise, more will be captured and compromised. If citizens remain cynical but passive, those who play the game best will write the rules.

The alternative path, in which destabilization is made more costly and less rewarding, will not be easy. It will require a degree of self scrutiny and reform that American political culture has tried hard to avoid. It will involve naming the ways in which allies have contributed to the corrosion of US democratic resilience, not just focusing on enemies. It will require accepting that scandals like Epstein’s are not detours from the story of power, but part of its central narrative.

The first step in any strategic response is to see the game that is being played. Only then can new strategies be devised that give a different answer to the core question facing a dominant but internally fragile power in a world of opportunistic rivals.

Will the United States continue to treat the erosion of its stability as an unfortunate background condition, something to be managed around the edges while business as usual continues. Or will it recognize that it is now the main arena of conflict, the central board on which others are making their moves.

If it chooses the second, there is still time to do what game theorists always recommend when the current equilibrium is intolerable.

Change the game.

PART XI: INSIDE THE STRATEGIC CALCULUS

So far the story has been told mostly in words. To see how the logic of destabilization operates under the surface, it is useful to make the choices and payoffs a bit more explicit, even if only in rough, intuitive terms.

Imagine first a very simple game between two players: the United States and Russia.

Each round, Russia can choose to interfere in US domestic politics or to refrain. The US can choose to invest heavily in defense and punishment of interference, or to react weakly.

If Russia refrains and the US invests heavily in defense, both sides lose some resources, but the political relationship is relatively stable. If Russia refrains and the US reacts weakly, both conserve resources, and the relationship may even improve.

If Russia interferes and the US reacts strongly, Russia may experience sanctions or other penalties, while the US absorbs some disruption but signals that the cost of interference is high. If Russia interferes and the US reacts weakly, Russia gains at low cost. It damages US cohesion and pays little.

In this stripped down model, Russia will tend to interfere whenever it believes the US response will be weak or inconsistent. The US will tend to respond weakly when the domestic costs of confrontation are high, for example when enforcing penalties would disrupt trade or alienate partners.

Now complicate the picture.

Add other players such as China, Iran, and Israel. Add the fact that the US political system is internally divided, so that its response depends on who holds power and how they themselves benefited or suffered from foreign interference. Add a media ecosystem that can cast any defensive move as partisan sabotage or as a threat to free speech.

Suddenly, from Russia’s vantage point, the expected cost of interference shrinks further. Even if the US occasionally punishes, the punishment will be uncertain and delayed. The benefits, in the form of increased division and mistrust, accumulate regardless.

In game theory terms, the structure resembles what is called a repeated prisoner’s dilemma with asymmetric information and weak enforcement. Defection, here meaning interference, becomes the dominant strategy for any player that places little value on the long term health of US democracy.

From the US point of view, things look different.

The US benefits from a stable international system where elections are not routinely undermined by foreign actors. But it also benefits, in the short term, from good relations with certain countries that may occasionally cross the line. Penalizing every infraction might satisfy abstract fairness but cause diplomatic and economic problems.

There is a natural temptation, then, to respond selectively, to prioritize other interests over the health of domestic institutions. That temptation is amplified when parts of the US elite profit from the status quo.

In game theory, this is recognized as a commitment problem. The US cannot credibly commit to always imposing heavy costs on interference, because sometimes it will prefer not to. Other players understand this. They adjust accordingly.

The equilibrium that emerges is not because anyone sat down to design it. It emerges because each player, at each moment, follows what seems locally rational, given their beliefs and constraints.

Russia interferes because it expects low punishment and decent payoffs. Israel runs a covert influence campaign because it believes it must lock in support under intense pressure. US platforms hesitate to clamp down on manipulative content because such content is lucrative. US politicians hesitate to reform the system because they fear losing their own advantages.

When you step back, it looks like fate. When you step in, it looks like small, understandable choices.

PART XII: 2016 AS A STAGE GAME

To make this more concrete, consider the 2016 US presidential election as a single stage in the larger repeated game.

On the Russian side, planners looked at a set of conditions.

The United States was highly polarized. Trust in institutions had been eroding for years. Social media had become a primary vehicle for political communication, with weak safeguards. One candidate, Hillary Clinton, was clearly associated with the establishment and with policies that had constrained Russia. The other, Donald Trump, was a wildcard whose campaign rhetoric included praise for Vladimir Putin and skepticism of NATO.

In that situation, Russia’s payoff matrix for interference might look something like this:

If Russia interferes, and the interference helps Trump, Russia gets a US president less likely to unite Europe against Moscow and more likely to cause internal turmoil. If Russia interferes, and the interference fails, Russia has still deepened US mistrust and has gathered valuable intelligence on US reactions. If Russia does not interfere, the outcome is left to chance.

From that vantage point, the costs of interference, primarily the risk of sanctions and reputational damage, were worth bearing. After all, Russia had already been hit with sanctions for its 2014 annexation of Crimea. Its relations with the US were already strained. The marginal risk of being caught was not zero, but it was not overwhelming.

On the US side, decision makers faced their own matrix.

Interference had to be acknowledged and countered. But publicizing the scale and nature of the interference risked being seen as taking sides in the election. Sanctions and public retaliation could invite escalation in cyberspace. Platforms that discovered evidence of foreign activity worried about appearing biased. Newsrooms faced difficult judgment calls about publishing leaked material that had been obtained illegally.

Within US institutions, there were also diverging beliefs. Some saw foreign interference as a central threat. Others believed it was being exaggerated. Some assumed that US voters would reject obvious propaganda. Others believed voters were more vulnerable.

The result was a fragmented, often hesitant response. Some agencies moved quickly to trace intrusions and warn state election officials. Others minimized the problem. The sitting administration chose a relatively cautious approach in public, fearing that stronger statements would be perceived as meddling in favor of one candidate.

In this stage of the game, Russia’s expectation that interference would be low cost and high leverage was borne out. Its actions are likely to have influenced the informational environment in which voters and elites operated, even if they did not single handedly determine the result.

For Russia, this stage is then incorporated into its beliefs about the next stages. It learns that US responses are divided and slow. It learns that social media manipulation, even when exposed, does not lead to devastating consequences. It learns that some US actors will even amplify its narratives for domestic advantage.

Game theory emphasizes learning in repeated games. Each round not only produces immediate payoffs. It changes what players believe about each other’s types and future behavior.

By the time the 2020 election came around, Russia had had four years to refine its strategies. The US had four years to harden its defenses. Both made adjustments. The interplay between them defined the new stage.

The lesson is not that Russia has perfect control over outcomes. It does not. The lesson is that, given the structure of incentives, it would have been surprising if Russia had not interfered.

PART XIII: THE ISRAEL–RUSSIA–US TRIANGLE IN SYRIA AND BEYOND

Another arena where strategic logic clarifies messy reality is the triangular relationship among Israel, Russia, and the United States around Syria and the wider Middle East.

Syria is a battlefield, but also a bargaining table. Russia supports the Assad regime and maintains military assets there. Israel, for its part, sees Iranian forces and weapons in Syria as a serious threat. It conducts periodic airstrikes to disrupt those networks. The US has its own forces and allies in the region and seeks to limit both Iranian and jihadist influence.

From a strictly military perspective, Russia could attempt to block Israeli operations, risking direct confrontation. Israel could ignore Russian presence and fly as it pleases, risking accidents. The US could try to push Russia out, risking escalation.

Instead, what emerged was a deconfliction system. Russian and Israeli officers coordinate to avoid accidental clashes. Israel reportedly notifies Russia about planned strikes to ensure that Russian assets are not hit. Russia complains about some Israeli actions, but generally tolerates them. The US, while not a party to the coordination mechanism, is well aware of it.

In game theory terms, this is a tacit cooperative arrangement in a larger conflict. Each side recognizes that open conflict between Russia and Israel would be costly and unpredictable. Each therefore finds it rational to accept a limited, managed level of friction.

The costs and benefits are uneven. Russia gains status as a power broker. Israel gains freedom to operate against Iranian targets while avoiding Russian defenses. The US gains a slightly more predictable environment.

At the same time, the arrangement creates leverage.

Russia can threaten to suspend or downgrade the coordination if it wants to pressure Israel on other issues, for example when it is unhappy with Israeli rhetoric about Ukraine. Israel, aware of its reliance on US aid and of Russia’s role in Syria, must balance its statements and moves toward Moscow.

The US, watching this, has mixed incentives. It wants Israel to prioritize its alignment with Washington. It also wants to avoid pushing Israel into a corner where it feels compelled to accommodate Russia more fully. During crises, these competing pressures become visible.

This is another example of a multi level game. Israel plays one game with the US and another with Russia. Moves in one game affect constraints in the other.

Destabilization strategies play into this triangle as well.

Russia can seek to influence Israeli public opinion and politics through its large Russian speaking diaspora in Israel, though that population is diverse and not automatically loyal to Moscow. It can also use state media and diplomatic channels to amplify divisions inside Israel over the proper stance toward the Ukraine war.

Israel, in turn, can use its own diaspora networks and influence tools to shape perceptions about Russia in the US. For instance, by emphasizing certain narratives about shared threats or by downplaying criticism of Israel’s relationship with Russia.

The United States is the constant reference point. Both Russia and Israel measure their payoffs partly in terms of how close they are to Washington and how much they can shape Washington’s choices.

Seen from above, this triangular relationship reveals how complicated the idea of a coordinated Israel–Russia strategy against the US really is. On some specific issues, such as limiting US pressure on both Moscow and Jerusalem at the same time, their interests may align. On others, such as Iran’s role in Syria or energy markets, they are sharply at odds.

Yet, in the wider destabilization game, the effect of their separate moves often pulls in the same direction. Russia seeks to divide and distract the US. Israel seeks to bind the US tightly to its own security agenda, even at the cost of US credibility elsewhere. Both, in different ways, constrain Washington’s freedom of action and deepen its entanglements.

In each case, the calculi are rational at the narrow level. Neither state sits down to coordinate against the US as an abstract enemy. They pursue their own goals. The combined effect, however, is a United States that finds it harder to act as an independent, coherent agent.

PART XIV: SCENARIOS FOR THE 2030s

If we project the logic of the destabilization game forward, several possible futures for the United States and its strategic environment suggest themselves.

The first is a scenario of deepening erosion.

In this path, the US fails to undertake serious reforms. Social media platforms remain loosely regulated. Elite impunity continues more or less unchanged. Campaign finance and lobbying grow even more opaque. Public trust in institutions continues to decline, punctuated by cycles of protest, scandal, and backlash.

Russia and other adversarial states continue to innovate in information operations and cyber tools. They make use of advances in artificial intelligence to generate more convincing fake personas and content. They develop new ways of combining digital and physical pressure, for example by exposing compromising material at moments of political vulnerability.

Allies, including Israel, continue to experiment with covert influence where they believe vital interests are at stake, confident that any exposure will yield only temporary embarrassment.

In such a scenario, American politics in the 2030s could be marked by:

Frequent disputes over the legitimacy of elections, with both sides accusing each other of foreign collusion.

Legislatures partially paralyzed by internal purges and loyalty tests.

Growing regional separatist and nullification movements as trust in federal institutions decays.

A foreign policy that lurches between isolationist retrenchment and reactive shows of force, as coherent strategy becomes harder to sustain.

In game terms, this is an equilibrium in which defection and manipulation dominate. It is stable in the narrow sense that no single player has an incentive to unilaterally switch to cleaner play. It is unstable in the deeper sense that the underlying system may eventually break.

A second scenario involves partial adaptation.

In this path, the US incrementally strengthens its defenses. Some reforms to digital platforms increase transparency. Some high profile elite scandals lead to stronger enforcement of anti corruption laws. A few meaningful steps are taken toward campaign finance transparency. A new generation of political leadership takes the threat of foreign interference more seriously.

Russia and others still play the destabilization game, but find it somewhat harder. Some operations are deterred at the margin by clearer red lines and more predictable penalties. Some elite networks become more reluctant to take obviously compromising offers from foreign sources.

Under this scenario, American politics in the 2030s might still be chaotic, but the worst risks are managed. Elections continue to function. Public distrust remains high but does not tip into outright rejection of democratic procedures. The US retains enough internal coherence to play a leading role in managing global crises.

From a game theoretic view, this is like moving from a prisoners’ dilemma to a slightly more cooperative repeated game, in which mutual restraint on the most damaging moves is sustained by a mix of deterrence and norms. It is not perfect, but it is survivable.

A third scenario imagines more fundamental change.

Here, the destabilization game triggers a large scale domestic rethinking. Perhaps a scandal combining elements of foreign influence, elite criminality, and institutional breakdown proves too big to ignore. Perhaps a near miss in a foreign crisis shocks the public into seeing the connection between internal rot and external risk.

In response, a coalition forms across parts of the political spectrum for systemic reform. It might include:

A serious overhaul of social media regulation, treating certain aspects of the digital public sphere as infrastructural and subject to public obligations.

Major anti corruption and transparency legislation, including real enforcement teeth.

Electoral reforms that reduce gerrymandering, make representation more proportional, and dilute the power of extremist minorities to paralyze governance.

Stronger protections for whistleblowers and investigative journalism, including specific provisions for those exposing foreign influence.

This scenario is the most uncertain, because it requires a level of political will and coordination that has often been lacking. But it is also the one in which the payoff matrix shifts most strongly.

If the US can credibly raise the expected cost of manipulation while lowering the expected benefits, many foreign actors will treat destabilization as less attractive. They may continue to interfere, but less aggressively. Allies will think twice before crossing certain lines. Domestic elites will find themselves more constrained by legal and reputational risk.

In this future, the US would not be immune to destabilization, but its internal resilience would be higher. The gun would still be there, but its grip weaker.

PART XV: A NARRATIVE RETURN TO THE ROOM

To bring the abstract back to the concrete, picture a scene that might already have happened, or might yet happen, somewhere between the surface and the depths of power.

A small dinner at a townhouse in a major city. The host is a wealthy financier with a complicated past. The guests include a senator on an important committee, a tech founder whose platform quietly shapes what millions see and think, a former intelligence official running a private security consultancy, an energy executive with projects in Eastern Europe, and a visiting dignitary from a foreign capital.

The conversation ranges widely. Officially it is off the record. They talk about regulation that might be coming. About elections and public mood. About wars abroad, including Ukraine and the Middle East. About scandals that might break and those that have been quietly dealt with.

Everyone in the room understands, at some level, that this is not just socialising. Information is being exchanged. Signals are being sent. Alliances are being tested. Each is a player in a game that includes the others.

The foreign dignitary listens closely when the senator talks about constituents’ fatigue with foreign aid. The tech founder picks up on what kind of content the former intelligence official believes is most dangerous. The energy executive mentions, casually, that certain jurisdictions have particularly lax enforcement of money laundering rules. The host lets slip a story about another guest, not present tonight, that reveals something about their private life.

This is the level at which many pivotal decisions are shaped. Long before they appear as talking points on television or as line items in a budget bill. It is also the level at which destabilization strategies and elite capture meet.

If a foreign service has a source in that room, or if a participant is already compromised by other dealings, the game is more complex still.

Maybe the visiting dignitary has been briefed by his own security apparatus about the vulnerabilities of the host. Maybe he knows that the tech founder’s company depends on access to his country’s market. Maybe the senator has reason to fear that old travel records could be brought into unflattering light.

Viewed from outside, decades later, such evenings are easy to dismiss as gossip. Viewed from inside, as they happen, they are the threads that tie together domestic politics, foreign influence, information architectures, and personal weakness.

The Epstein circle was one such environment turned up to eleven. There are many more mundane ones.

Game theory reminds us that every move in a game is made by someone who thinks they are being rational. Epstein’s guests thought they were networking. Russian troll farm workers thought they were doing their jobs. Israeli digital contractors thought they were defending their country. US tech executives thought they were maximizing shareholder value. Politicians thought they were winning.

The tragedy is that those individual rationalities, combined, can produce collective outcomes that almost no one, at least publicly, claims to want.

An America permanently on edge, losing confidence in its institutions, unable to separate genuine allies from opportunistic manipulators, and tempted to retreat from a world that still depends on its contradictions.

That is what it looks like to be under the gun of a destabilization strategy that is not a singular plot but a pervasive method.

The task now, for those who still believe in the possibility of a more honest politics, is to recognize the method, explain it clearly, and begin to design institutions and norms that can counter it.

That means more than frictionless exposure of scandals and villainies. It means a long, deliberate effort to realign incentives so that, in the next round of the game, fewer players find it profitable to aim at the same fragile target.

The United States cannot opt out of being a central player. It can, however, choose whether it continues to play the game blindfolded, or whether it finally learns to look at the board.