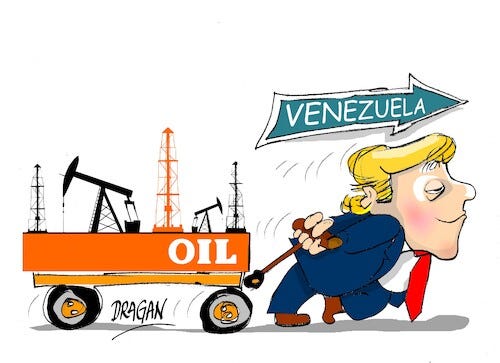

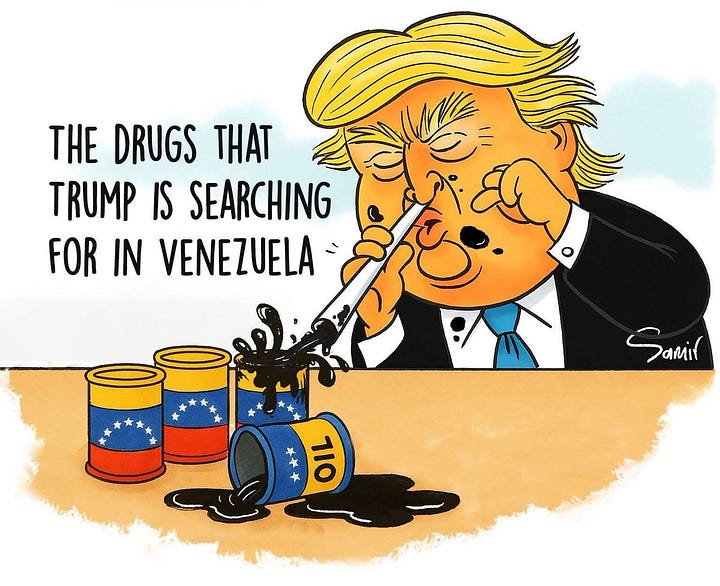

Donald Trump Will Run Venezuela

How a regime‑change fantasy collides with geology, sanctions, and OPEC politics.

Trump’s decision to say the United States will “run” Venezuela after Nicolás Maduro’s capture turns what was already a risky energy gambit into an open experiment in occupation politics built around …